Auyán Tepui

Auyán Tepui is one of the largest and most expansive tepuis in Venezuela, home to the tallest waterfall in the world, Angel Falls. The plateau comprises 257.5 square miles of rock and forest with numerous endemics species including abundant carnivorous plants. While there is only one species of Heliamphora, Heliamphora minor, there is a unique and elusive form of this species covered with fuzz. Unlike the other tepuis which required helicopter dropoff, this tepui would be scaled on foot over the next week.

The Looming Giant

After returning from Aprada tepui, we spent the night in the local village. Then, another Cessna flight to the village at the base of Auyán Tepui. This giant tepui would require backpacking for a full week. We loaded up on supplies with a new crew of porters, and set off the following day.

While leaving the village in the morning, we met their adopted baby tapir named “Tato”. It was found orphaned in the forest (it’s mother likely hunted for food), and the locals brought it back to raise as a pet. He was docile and sweet — one of the highlights of that trip.

Many miles of trekking across the hot sabana finally led to the beginning of the base of the tepui. The local Pemón will regularly do controlled burns to keep the grasslands under control. The equatorial sun is hot.

Here we began to encounter our first carnivorous plant. This is the carnivorous bromeliad, Catopsis berteroniana. Though the degree of carnivory is debated, it has been shown to trap insects within the urn. Regardless, they immediately stood out from the landscape with intensely vibrant yellow-green color. When the sun illuminates the leaves, it literally glows from its epiphytic perch amongst the trees.

To survive with such a limited root system, these must rely on the morning fog and regularly rainfall. Certain trees could be home to dozens of individuals.

The weather gave a clear view of the plateau ahead of us, with brilliant Catopsis welcoming us from the trees. This was the edge of the gradual slope leading to the base of the cliffs where varied habitats began to emerge.

By a small creek with short trees, we found Drosera kaiturensis displaying its “splash cup” seed pods. When ripe, the pods split open facing upward waiting for rain to strike and forcefully distribute the seeds.

Sunset in this unique landscape ushered in the end of the first day. We camped by a small palm frond hut in a clearing.

Mornings are characterized by dense fog obscuring the path. By this time, the fog has already lifted enough to see the forested base, but the rest of the tepui is hidden.

Within the dense grasses were Drosera roraimae. This amazing species was found on every other tepui and is extremely variable in phenotype, though typically orange to red in color. The tall stems on some of these specimens could indicate decades of growth.

At the base of almost all tepuis, there is at least a band of dense forest. Many animals inhabit this area since the savannah offers little to no protection from the sun or predators. It is possible that most of the savannah was once this type of forest before ancient humans cleared parts of the land.

As the gradual slope steepened, the forest opens up with huge bolders and rock formations offering vantages to look up at the cliffs above.

Camp for night two was under an overhang, sheltered from any potential rain, but more importantly flat ground which is almost non-existent on the slope. While this day was entirely uphill, the next day would be the actual climb up the cliffs.

Utricularia began to appear in the moist, shady vegetation overshadowed by the cliff of Auyán. Open areas had bromeliads containing large specimens of Utricularia humboltii (third photo).

Wet walls with mosses (sometimes carpets of sphagnum) could support populations of Drosera roraimae in patches with enough light.

This diagonal crack would be the route to the summit. From this distance, it looked like jagged rock and vegetation.

This diagonal crack would be the route to the summit. From this distance, it looked like jagged rock and vegetation.

The crack was a deep canyon full of giant bromeliads, ferns, and other strange plants. It was around this point where my porter was overcome with a recurrent bout of malaria and had to return to the village. I had to take my full pack and recombine it with my day pack to climb the most difficult part of the route.

The last few hundred feet of elevation had to be traverse by boulder hopping on slippery, plant-obscured rocks. A section had a rope climb up a vertical face for 10 feet which took all my remaining strength with a full pack weighing me down. This part was the most harrowing and dangerous of the whole route.

The Plateau

The plateau, while limited in elevation change, is still endlessly craggy and eroded with hidden pockets of vegetation and deep crevasses.

Once at the plateau, Sundews were growing in different niches. Drosera hirticalyx (first), Drosera felix or kaiturensis (second), Drosera arenicola (third).

Some large Heliamphora minor found in a fluffy patch of lichens. While this is the only species found on Auyán, there are two distinct forms.

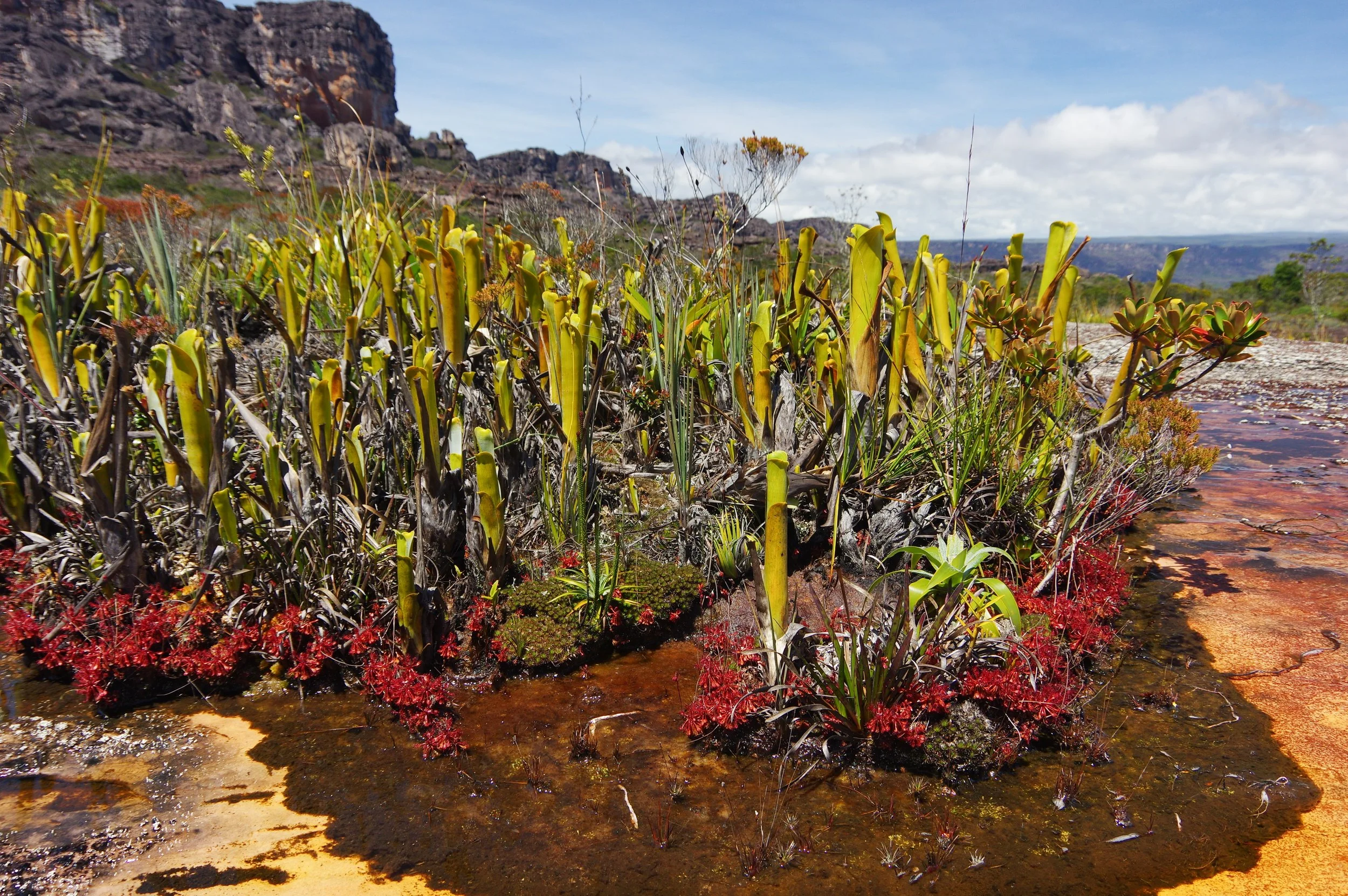

The flat areas were characterized by the brilliant yellow-green of the carnivorous bromeliad, Brocchinia reducta. The tubes act as passive pitfall traps to acquire nutrients in the rain-leached environment. Though many grow this species in cultivation, no one achieves the tight shape and yellow color induced by extreme equatorial sun.

This dense colony of Drosera arenicola was growing out the side of a sandstone face and was a unique find from the usually terrestrial, wet sand-growing species.

There are at least 4 different species on the plateau, with potentially more that are undescribed. First and second photo: Drosera arenicola. Third photo: Drosera roraimae.

The Heliamphora could sometimes be found flooded in flowing water, demonstrating how they received the name “Marsh Pitcher Plant”.

The Summit

While Auyán Tepui is primarily a plateau, it does have distinct terrain and local peaks. This area was known as “El Dragón” and required a sketchy, slippery climb up the sandstone cliffs to a marsh that contained the mythical, “hairy” pitchers of Heliamphora minor var. pilosa.

Interspersed with regular forms, the “hairy” var. pilosa form has coarse hairs on the interior like some forms of pulchella, but distinctly has hair in the outside of the pitcher as well. This make its unique amongst the Heliamphora.

The dense clumps of Heliamphora minor var. pilosa were spectacular (for Heliamphora enthusiasts) and worth climb in foggy, rainy conditions. We returned to camp for the last night on the tepui.

The final day atop Auyán Tepui was met with bright sun. These patches of vegetation had Utricularia in the submerged sludge, Drosera roraimae at the margins, and Brocchinia reducta and the occasional Heliamphora in the dense plants at the center.

With clear weather, the view of the surrounding tepuis and gran sabana was finally revealed.

The wide open savannah was a reminder of the 2 day trek back to the village, now in the tropical sun and heat.

After one more night camping under the cliffs, we continued all the way back to the grasslands. The clouds would quickly come in and cover the tepui, shrouded in mystery again.

A short Cessna flight to view Angel Falls then a long off-road drive to the highway, stopping along the way to view the charismatic Heliamphora heterodoxa in the Gran Sabana. From there, a long highway drive back to Santa Elena de Uairén, a border crossing back into Brazil to Boa Vista, then a flight to Manaus. The long journey to five tepuis over more than two weeks was complete.